Introduction

The Night Elvis Didn’t Just Perform—He Connected a Planet

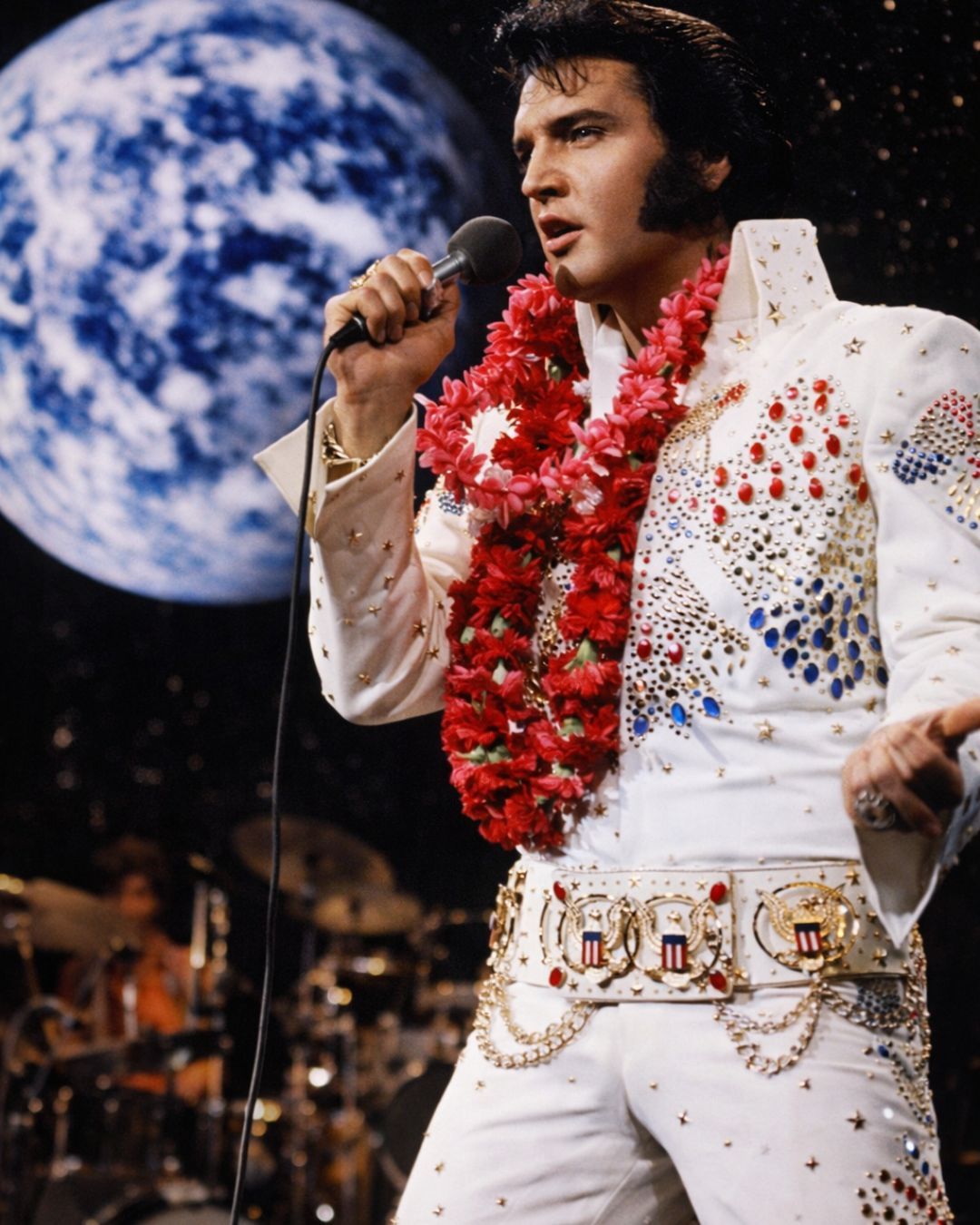

“Is The World Ready For This?” — In 1973, Elvis Presley’s Aloha From Hawaii Became The First Concert Beamed Live Worldwide, Reaching 40+ Countries And Rewriting TV History Forever. In 1973, Elvis didn’t just take the stage—he took the planet. Clad in his eagle cloak, the King beamed his “American Trilogy” to over a billion people, outdrawing the moon landing. Was the world ready for the first global supernova?

Even if that headline reads like pure fireworks—and parts of it have been repeated with a little extra shine over the decades—the core story remains one of the most fascinating collisions of music, technology, and pop-culture ambition ever attempted. Aloha from Hawaii via Satellite was a landmark: a major Elvis concert staged in Honolulu and transmitted by satellite to international audiences at a time when “global live entertainment” was still closer to science fiction than routine television.

What’s especially interesting for older, attentive listeners is how the legend and the reality weave together. The concert itself aired live via satellite primarily to audiences in Asia and Oceania on January 14, 1973, while much of Europe saw it later on a delay—and American viewers didn’t get the NBC special until April 4, partly due to scheduling concerns. That doesn’t make the story smaller. If anything, it makes it more human: an enormous technical gamble shaped by time zones, broadcast politics, and the limits of the era.

Then there’s the famous question of “how many people watched.” Promotional claims often soared—figures like 1.5 billion viewers and dozens of countries became part of the folklore—but even contemporaneous discussions and later analysis have pointed out the math problems and suggested much lower worldwide totals (often cited in the hundreds of millions or less). The truth is: whether it was 150 million, 300 million, or something higher, it was still a breathtaking reach for a single performer in 1973—and it helped define what a televised concert could be.

Musically, that’s where Elvis matters most. The technology is the frame; the voice is the painting. In those peak moments—when the band locks into a stately groove and Elvis leans into the drama of a piece like “An American Trilogy”—you hear an artist performing with the weight of history on his shoulders, yet still aiming straight for the heart. And the image—the eagle suit, the ceremonial posture, the sense of occasion—wasn’t just costume. It was Elvis understanding television as theatre, and theatre as mythmaking.

So, is the world “ready” for a first global supernova? Maybe the better question is whether the world recognized what it was seeing in real time: a superstar using the most advanced broadcast tools available to turn a concert into an international event—one that still echoes whenever artists try to “go global” with a single performance.