Introduction

They Built the Statues Because Silence Wasn’t Enough — Elvis, Memphis, and the Kind of Memory That Won’t Sit Still

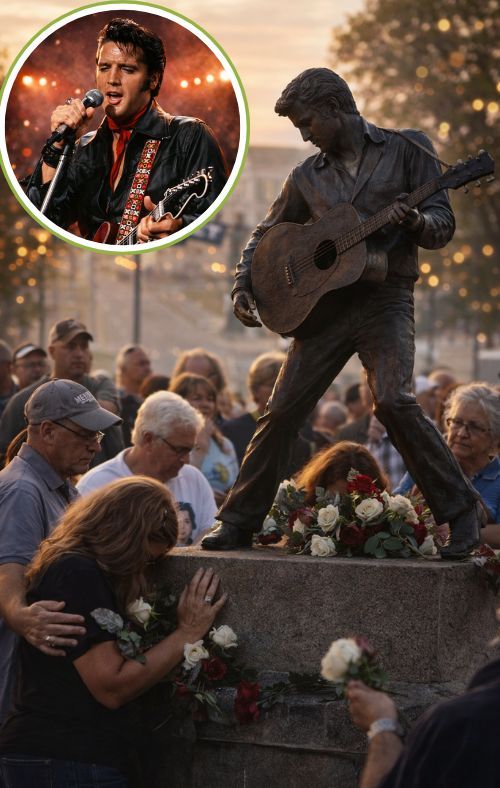

Some legends are preserved in museums, filed neatly into a past tense that feels safe. But Elvis in Memphis has never worked that way. The memory refuses to behave. It doesn’t stay behind glass, and it doesn’t flatten into a souvenir. That’s why your opening idea is so powerful: They didn’t build statues to keep him frozen in time. They built them because silence wasn’t enough. When a city raises bronze into the air, it isn’t only honoring a man—it’s admitting that the absence still has weight.

Across Memphis and beyond, these monuments stand in places where the story still feels physically present: Beale Street, the roads leading toward Graceland, corners where footsteps once carried a kind of electricity people still talk about as if it happened yesterday. And that’s the strange, enduring truth about Elvis: the culture keeps moving forward, but it keeps circling back to him. Not because we ran out of new music, but because what he represented—risk, reinvention, hunger, and a certain American permission to become something bigger than your beginnings—still feels unfinished.

What makes statues different from billboards or posters is their quiet. They don’t sell you anything. They don’t demand your attention. They simply wait. At dawn, before the crowds arrive, you can imagine what you describe so well: a pause in the air, as if history is holding its breath. That’s not sentimentality; it’s atmosphere. Certain places carry residual meaning the way old churches do—spaces where people have prayed, grieved, celebrated, and kept returning. In that sense, the monuments aren’t just art. They’re landmarks of collective feeling.

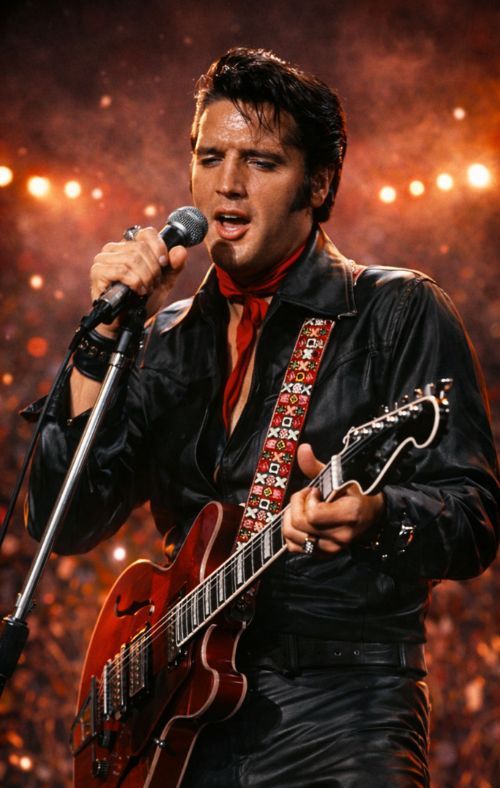

For older listeners, especially those who remember Elvis as a living presence rather than a permanent icon, these statues can stir a particular kind of emotion. Not the shallow kind—more like the ache of realizing how many decades have passed, and yet how immediate his impact still feels. Elvis is often reduced to caricature in pop culture: jumpsuits, headlines, impersonations. But in Memphis, the remembering tends to be more grounded. It’s less about myth and more about presence—young, restless, mid-stride, as you write, guitar angled toward a future he changed forever. The statues capture motion, not stillness. They seem to suggest that what made him remarkable wasn’t simply the voice, or even the fame, but the forward-leaning momentum: the sense that he was always reaching past the limits of what people expected a Southern boy to become.

And then there’s the deeper question your paragraph asks—one that cities and fans still return to because it doesn’t have a clean answer: how do you honor someone who never really left? When an artist becomes a reference point for identity—regional pride, cultural memory, family stories, the soundtrack of a first love or a first heartbreak—death doesn’t erase the relationship. It changes it. People continue to visit, not merely to look, but to feel connected to the part of themselves that Elvis awakened.

So this isn’t a story about stone and metal. It’s a story about why we build markers when words fail. Statues aren’t meant to replace a life; they’re meant to hold space for the echo of it. In these quiet corners, Memphis doesn’t shout Elvis’s name. It keeps a place for it—standing tall, listening—while the world returns again and again to remember what it felt like when the music first changed everything.