Introduction

The Singer Who Made Highway Miles Sound Like Scripture: A Voice With Chrome and Dust: Dwight Yoakam and the Poetry of the Open Road

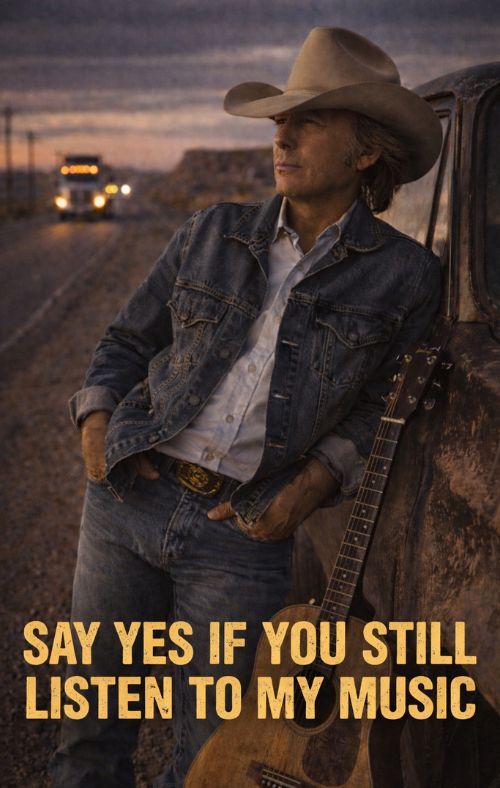

Some singers arrive sounding like they were built in a studio—every note sanded smooth, every phrase designed to impress. Dwight Yoakam arrived sounding like he’d already been somewhere. Not just geographically, but emotionally. There’s a traveled quality to his voice, a tone that suggests neon lights seen too late at night, coffee gone cold on a dashboard, and the kind of loneliness you don’t dramatize because you’ve learned to live with it. That’s why A Voice With Chrome and Dust: Dwight Yoakam and the Poetry of the Open Road feels like more than a clever phrase. It’s an accurate description of what his music does to the listener: it puts you in motion, and it keeps you there.

Yoakam’s genius is that he never needed to shout to feel urgent. He understands restraint—the subtle tightening in a vocal line, the way a lyric can land harder when it refuses to beg for attention. In many eras, country music has leaned toward big gestures and clean resolutions. Dwight, on the other hand, has often lived in the in-between: the last call moment, the goodbye that doesn’t come with closure, the road that promises freedom but also delivers distance. His songs don’t insist you admire him. They invite you to sit in the passenger seat and look out at the world with him.

And what you see, through that windshield, is America—real America—changing mile by mile. Not the postcard version. The lived-in version. Truck stops and small towns and parking lots behind clubs. The stretch of highway where your thoughts get louder because there’s nothing else to compete with them. Older listeners recognize this terrain immediately, because life teaches you something younger people often miss: freedom and solitude can share the same seat. The road can be a refuge, but it can also be an honest mirror. Dwight’s music doesn’t pretend otherwise. It doesn’t romanticize the miles as pure escape. It treats them as survival—movement as a way to keep going when staying still would make the truth too heavy.

That’s also why his catalog doesn’t feel trapped in any one decade, even when the production points to a particular time. The emotional engine is timeless: wanting, leaving, returning, regretting, repeating. Yoakam’s songs feel tied to motion rather than fashion. While the wider industry often chased reinvention, he carried a harder-to-fake quality: a clear-eyed understanding of what it costs to keep driving forward. There’s a kind of dignity in that—music that refuses to flatter the listener, but still offers companionship.

So when you hear Dwight Yoakam, you’re not just hearing country music. You’re hearing a map—drawn in chrome reflections and desert light—of how people endure. A voice with dust in it, yes, but also with purpose. Because even when the songs are lonely, they don’t collapse. They keep rolling. And for anyone who’s lived enough life to know the road isn’t always a choice—sometimes it’s simply what you do to survive—Dwight’s music still feels like home in motion.