Introduction

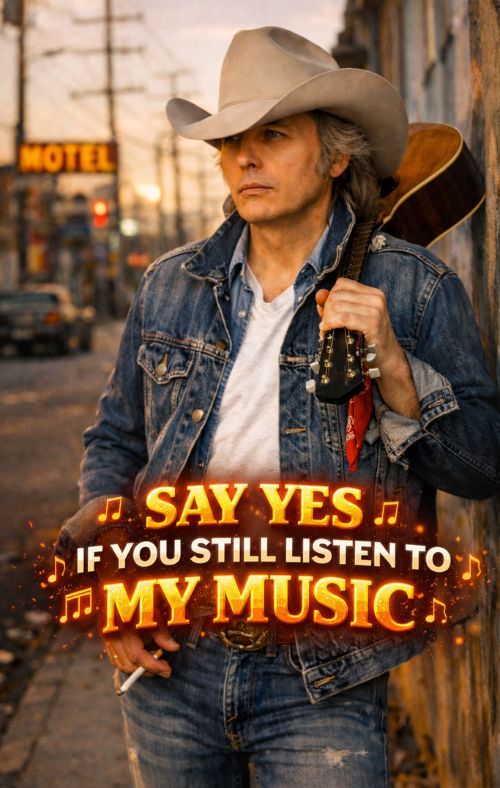

The Country Rebel Who Took the Long Way Around: Dwight Yoakam’s Los Angeles Detour That Changed Everything

The standard country-music storyline is almost a ritual: pack the car, drive to Nashville, shake hands, wait your turn, and hope the gatekeepers recognize you. But Dwight Yoakam’s story doesn’t follow that script—because he didn’t believe the script deserved to be followed. That’s the tension at the heart of “HE DIDN’T GO TO NASHVILLE—HE OUTRAN IT”: How Dwight Yoakam Built a Country Revolution from Los Angeles. It’s not just a clever headline. It’s a map of how real artistic change often happens: not inside the system, but just outside it, where the rules don’t apply as neatly.

Yoakam carried the Bakersfield sound—the sharp twang, the lean guitar bite, the working-class ache—into Los Angeles, a city that country traditionalists didn’t consider “legitimate” ground. For a lot of people, that choice looked like a mistake. Nashville was the center of the industry machine; L.A. was where country music went to get diluted, they said. But Yoakam wasn’t interested in dilution. He was interested in ignition. And Los Angeles, for all its contradictions, offered him something Nashville could not: a space to collide with other scenes and come out sharper.

Picture the rooms he played: rock clubs, bar stages, mixed crowds that weren’t arriving with a country rulebook in their pockets. These were audiences that didn’t automatically respect twang or tradition. They had to be convinced in real time. That’s where Yoakam’s stubborn identity became his advantage. If you can make Bakersfield-style country hit in a room that isn’t “supposed” to want it, you’re not just repeating tradition—you’re proving it has power. The twang didn’t ask for permission. It simply showed up, loud enough to be undeniable.

Of course, the cost was real. Industry gatekeepers questioned him. Purists doubted him. There’s always suspicion when an artist refuses the approved route—especially in a genre that can confuse tradition with geography. But Yoakam’s outsider path became the secret weapon. He wasn’t trying to fit the system; he was building his own, piece by piece, by playing for people who didn’t owe him anything. That kind of apprenticeship—earned in indifferent rooms—creates a different kind of performer. It teaches you economy. It teaches you urgency. It teaches you how to make the song do the talking.

For older listeners, this is the career story that resonates because it mirrors real life more than a fairy tale does. Most meaningful success isn’t a clean invitation. It’s a stubborn insistence, repeated over years, until the world has to admit you were right. Yoakam didn’t find a lane waiting for him. He carved one—out of Los Angeles nightlife, Bakersfield memory, and a refusal to sand down the edges that made the music honest.

And that’s why his “detour” still feels like a revolution: it reminds us that sometimes the fastest way to change a genre is to outrun its center—and bring the truth back from the outside.